The Art Of The Deal: On the rise of the artist agent

By Natasha Degen

11/15/24

Back

THAT ART WAS CREATED for its own sake was our inherited ideal. For the better part of two centuries, artists and art institutions upheld this vision of art’s autonomy, elevated above quotidian life and unadulterated by base commercial concerns. Things were of course never so simple or pure; reality never quite lives up to the ideal. But the novelty of the present is only visible against this image of the past. Today’s “pop life”—the embrace of mass media, mass culture, and mass markets—has become so pervasive it largely passes unnoticed. No one so much as blinks when artists make advertisements and promotional videos, collaborate with luxury brands, direct feature films, or launch their own lines of clothing, eyewear, jewelry, toys.

As a sea change builds imperceptibly, it can be hard to grasp the significance of what is taking shape. But as history suggests, the seemingly spontaneous emergence of new roles in the art ecosystem offers tectonic evidence of the shifting ground on which art stands. The explosion of professional opportunities available to artists, and of commercial interests solicitous of their talents, has carved out a niche for a new figure at the juncture of these collaborations: the artist agent.

The emergence of the agent reflects both current market conditions—notably, the shift in attention and resources to living artists—and a longer-term drift away from art’s church-and-state separation from commerce. That these trends appear to extend into the foreseeable future suggests the possibility that, as in other talent-driven industries, agents may be here to stay. “This isn’t a fad—it isn’t going away—it is a natural progression,” Max Teicher of 291 Agency says.1 But a natural progression can also be a radical departure.

The first “art agents” emerged in Renaissance Europe to support buyers rather than artists. They were a motley crew of diplomats, secretaries, artists, and merchants who helped to source artworks and establish quality and valuation at a time when most art was commissioned rather than created on spec. Dealers would emerge later as “a special type of agent” for the newly affluent urban classes, as art historian Sandra van Ginhoven has written.2 They appeared first in Antwerp in the late sixteenth century, then in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century, ultimately superseding the agent. The open market, in which artists produced works for unknown buyers, required a new intermediary. Dealers fit the bill.

The changing market realities of each subsequent age have called for a reinvention, subtle or sometimes not so subtle, of the figures who stand at the intersection of artists and their buyers. Fast-forward to the 1980s when, as Diana Brooks of Sotheby’s reported, the number of “serious private clients” bidding at auction quadrupled in just two years, from 1983 to 1985.3 This influx of new buyers called out for a new sort of agent, the “art adviser.” The Association of Professional Art Advisors, founded in 1980, had grown from eight to forty members by 1987, and as the role professionalized in the decades that followed, art advisers became an art-world fixture.4 The APAA claims more than a hundred and seventy-five members today.

The artist agents of recent years look to play an analogous role on behalf of artists themselves. As the work of living artists came to dominate museums and the market, the operations overseen by successful artists ballooned. Their studios grew in size and their careers in complexity, requiring, among other things, vastly more communication and coordination with the institutional and commercial worlds. Galleries, in response, added artist liaisons to their staffs and created artist-relations departments. Meanwhile artists’ studio managers saw the scope of their responsibilities expand. In addition to supervising studio assistants and overseeing the fabrication of works, many now found themselves interfacing with multiple galleries, stewarding exhibitions, fielding requests from the press, and negotiating contracts. But issues remained. Artist liaisons are employed by galleries and ultimately prioritize their interests. Studio managers are often artists themselves, with little prior experience in business. The emergence of the artist agent reflected artists’ need for a dedicated advocate to represent their interests alone.

In 2015 the Hollywood talent agency UTA opened a division devoted to fine art, the first of its kind. “With popular recognition of contemporary art at an all-time high, a myriad of new opportunities—and new complexities—have materialized for studio artists,” the company explained in a press release.5 The following year its competitor WME acquired a 70 percent controlling stake in Frieze. In 2019 the third of the “big three” talent agencies, CAA, sold a majority share to Groupe Artémis, the Pinault family’s holding company, which also owns the luxury conglomerate Kering and Christie’s auction house, in a move that underscored the new synergy between the worlds of entertainment, fashion, and art. Flush with private-equity funding, the talent firms saw the moment as a propitious one to invest in art, although they would encounter economic headwinds in the years that followed. (UTA closed its fine-art division this past September.)

At the same time, smaller agencies that exclusively represent artists have multiplied. Some take on only established names, while others accept a wide range of clients, including recent art-school graduates and digital artists whose work circulates outside the traditional art world. Many agencies have been founded by gallery veterans who draw on their experience to help artists develop relationships with institutions, plan their estates, and grow their markets. While galleries offer similar services, they lack the capacity to give artists full-time, individualized support. Some agencies provide support that traditional art businesses do not, assisting with commercial licensing, brand partnerships, e-commerce, and speaking engagements. Today’s artists have largely come to embrace such opportunities, according to Marine Tanguy, founder of the MTArt Agency, whereas a decade ago “you really had to convince them, because people were telling them it’s a terrible thing to do.”6

The commitment to art’s autonomy has been eroding for decades, but the rise of the artist agent signals a more precipitous break. Many artists no longer look to major museums with the same starry-eyed reverence of years past. They see art as increasingly shaped and constrained by the marketplace, and they reject what they regard as the narrowness and rigidity of the art world itself. Some question whether their work needs the art context at all.

IN 1982 Ingrid Sischy and Germano Celant were already writing about “the merchandising of culture and the culturizing of merchandise” in this magazine’s pages.7 The occasion was a special issue devoted to art that existed outside the confines of the gallery, featuring essays on topics like the influence of fine art on pop music, graphic design in Poland’s Solidarity movement, and the “vulgar modernism” of animated cartoons and comic books. “Art becomes capable of appearing anywhere, not necessarily where one expects it, and of crossing over and occupying spaces in all systems,” Sischy and Celant explained. As if underlining their point, they put an Issey Miyake rattan cage bustier and matching skirt on the cover.

More or less concurrently, avant-garde retailer Dianne Benson opened her Dianne B. store in SoHo—one of the first boutiques in the art-centric New York neighborhood—and displayed the Miyake bustier in its window. Benson recognized the marketplace implication of a literal and figurative proximity to art, above all its capacity to infuse her store and its wares with a heady sense of downtown cool. By the end of the decade, Benson had commissioned work from Peter Hujar, Robert Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman, and David Wojnarowicz for her advertisements and catalogues. Artists across the scene experimented with retail projects and fashion collaborations. The pop-up “A. More Store,” sponsored by artist collective Colab, sold Kiki Smith severed-finger earrings, Barbara Kruger matchbooks, and Jenny Holzer Truism T-shirts. Jean-Michel Basquiat painted jumpsuits and sweatshirts for Patricia Field and walked the runway for Comme des Garçons. Keith Haring collaborated on designs with Vivienne Westwood and Stephen Sprouse and opened his Pop Shop, where he sold mass-produced art merchandise, including T-shirts, buttons, magnets, and skateboards.

Artists took to this melding of art and fashion for a number of reasons. Often they were friends with their creative collaborators or sought wider cultural reach. In some cases commercial work informed and deepened their artistic practice. (Sherman’s photographs for Benson, for instance, became the first works in her “Fashion” series, 1983–94, which she continued to expand over the next eleven years.) Beyond fashion and retail, the art of the 1980s evinced a new porousness to adjacent industries. Artists directed music videos, created installations for nightclubs, and appeared on television. Warhol was the unmistakable trailblazer, having directed and produced hundreds of films, managed the Velvet Underground, and embraced a constellation of commercial activities under the guise of “Business Art.”

“By the late 1970s, Andy Warhol’s contemporaries had lost interest in him and his artwork,” Peter McGough recalled in his 2019 memoir, but McGough and his peers “loved him.”8 Warhol found apt pupils in this rising generation. He taught them that commercial work could be an essential part of one’s artistic practice and demonstrated the value artists could bring to commercial projects, as with his 1985 painting of an Absolut Vodka bottle for Michel Roux, the CEO of Absolut’s US distributor. While Roux believed the work would make a great ad, his colleagues were skeptical, and initially the ad was only placed in a few art magazines. Roux’s intuition proved correct; the ad was a hit. Over the next few years, from 1985 to 1988, Absolut commissioned ads from other high-profile artists (Haring, Ed Ruscha, and Kenny Scharf among them). Its sales in the US grew at an annual rate of 42 percent, demonstrating the commercial potency of an association with contemporary art.

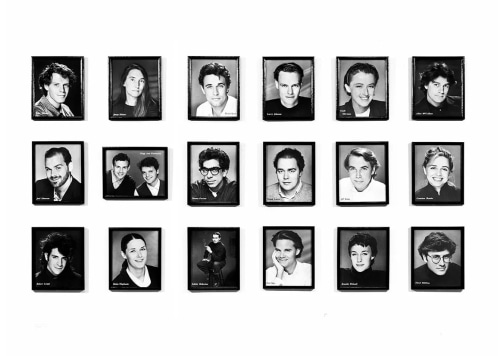

If artists could now act upon the broader culture, however, it could also act upon them. In his 1986 work Talent, David Robbins depicted the ’80s artist as a less aloof and rarefied figure than his bohemian predecessors, with a career rather than a calling. The work consisted of eighteen professional black-and-white headshots of his artist contemporaries, including Sherman, Holzer, Jeff Koons, and Robert Longo. “I functioned as the artists’ agent,” Robbins later recalled, “booking the sessions, seeing to it that the subjects arrived at the studio at their appointed hour, and paying the bill.”10 Every artist sat for thirty-six shots; Robbins chose the final picture. In each portrait the artist assumes the guise of an actor or entertainer, gazing into the camera with a pleased expression or a toothy smile. “Consistent with the formal look of headshots, which present people as amenable and easy to work with, the mood of each photograph is optimistic,” Robbins said.11 This optimism stands in opposition to the stereotypical image of the artist as heroic visionary, recasting each subject as a commodity. The artists’ complicity in their own commodification—reflected in the photographs’ promotional slickness—seemed to herald a new era. Robbins would later explicitly cheer on the convergence of “artist” and “entertainer,” anticipating a new figure whose work would occupy a middle ground between the two.

Read more here!