David Robbins on the importance of Hudson

ArtBook Blog

4/23/24

Back

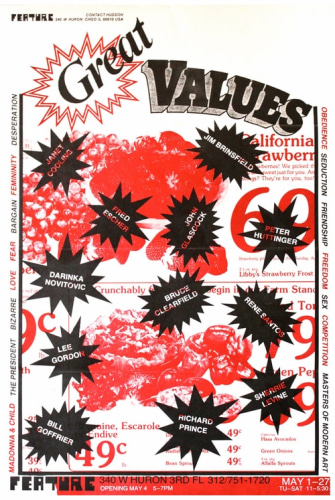

Most commercial galleries are open vessels, their offerings changing with the weather of trends. It’s business, and since the New and the Now are dependably self-replenishing, this model prevails. More rare are galleries that operate with a self-conscious existential dimension. If those walls could talk, they’d be asking “What is an art gallery for?” The proprietors of these theaters tend to be artists themselves, with the gallery their medium.In the late 80s, at the tail end of the era when the art world was still a world and not yet a safe, global, professionalized system, a few gallerists opened shops that were direct extensions of their personalities. In New York there was Colin de Land at American Fine Arts and, after he moved to Manhattan from Chicago, there was Hudson at Feature. Like the era, both have passed. Dressed in his mismatched plaid corduroy suit ensembles, the charming de Land was an art dealer who also seemed to be performing the role of an art dealer. He became celebrated for his synthesis of irony and authenticity. His gallery’s program was conceptual and strategic more than personal; in the 90s AFA was to some extent the New York outlet for Christian Nagel’s program in Cologne. (Read more on de Land in The Conditions of Being Art: Pat Hearn Gallery & American Fine Arts, Co., published by CCS Bard and Dancing Foxes Press.) Hudson, by contrast, wasn’t ironical and wasn’t playing games. What was on display with every exhibition at Feature was a man taking full responsibility for his subjectivity. What Hudson chose to exhibit was based entirely on his personal response—the idiosyncracies of his taste and what he wanted to explore. He firmly believed the power of the personal to be beyond all trends. For much of the 30-year life of Feature he was able to bend his corner of the art world to his essentially romantic purposes by force of will gracefully applied. Hudson didn’t do big post-opening dinners, he didn’t do wine and cheese, he didn’t schmooze, but at the gallery his desk was always placed in plain sight, without barriers, at which control center he was approachable. He did personally look at slides sent in by hopeful artists and hand write notes of encouragement. None of this would matter if he didn’t have an eye. Early in his Chicago days Hudson showed Charles Ray, Richard Prince and Jeff Koons. He brought Raymond Pettibon in from the punk music world. He discovered the wizard Tom Friedman. He exhibited a ton of women long before doing so became de rigueur. Occasionally Feature mounted exhibitions of Tantra paintings or showed raunchy Tom of Finland drawings. From the beginning his gallery showed, usually in two-person exhibitions, the kind of consciousness-altering work Hudson wanted to see released into the environment. (“What is an art gallery for?”) Ecstatic communion with the life-force, through art, led the way. He’d address the commercial considerations of his choices later. A new book about the man and his gallery, Hello We Were Talking about Hudson, has been published by Soberscove Press. Edited by longtime Hudson friend Steve Lafreniere, Hello gathers 35 interviews with Feature artists, employees,and friends to make a relaxed oral history, together with written remembrances from David Sedaris, Richard Prince, Bob Nickas, Gary Indiana and Hilton Als; Dike Blair contributes an interview with the late gallerist. A rich brew. Full disclosure: I was with Feature for 23 years, from its first year of operation, when the gallery was located in Chicago. But I wasn’t interviewed for this book; I was never integral to Feature’s story. It speaks for itself, though, that in the early 90s Hudson purged a lot of artists and I wasn’t one of them. I never knew what he liked about my work, but if you kept Hudson interested that was really all you needed to do. He left you alone to do your thing, however you needed to do it. And I left him alone, to do his, which he did beautifully. A score of times over the years he’d surprise me with a letter enclosing a much-needed check from a sale I wasn’t aware he’d been working on. That’s the way he did everything: quietly and effectively. To a point that he sometimes seemed another species, he was an evolved being, meditating twice a day and annually retreating to the Transcendental Meditation compound in Fairfield, Iowa. Evolved doesn’t mean perfect. He could indulge “the personal” overly much. There was a period when I began to find the shows at the gallery visually predictable—too much symmetry, too much mandala-like art. And challenged by the rise of the art fair as a sales model, he put off compromising too long. But his was a personal vision, and personal visions are not adaptable to all conditions. It was the end of an era. Colin was gone too. I’ll close with two stories of my Hudson. My 2004 exhibition at Feature, which was consciously a farewell to the art world, comprised large digital prints that grouped photos I’d taken of abandoned furniture awaiting pick-up at the curb in front of various affluent suburban homes. Were these pictures landscapes or still lives or, because furniture implied the human body, were they sly figure studies? We sold half the show. The remaining unsold, expensively framed pieces were packed up on the day after the show’s closing and, instead of entering the gallery’s inventory, they were carted to the 25th Street curb in front of the gallery, leaving them free to takers. Where a lot of gallerists would resist giving away examples from the same body of work that had just proved profitable, Hudson understood it as completing the art and responded with his velvety laugh. Another time, on a sultry summer evening in NYC, I was perusing the used-book stalls on 10th Street when I spotted Hudson footing it up Lafayette Street. H

DAVID ROBBINS

For three decades, in artworks and writing, David Robbins has promoted a frank, unapologetic recognition of the contemporary overlap between the art and entertainment contexts. His work Talent (1986) is widely credited with announcing the age of the celebrity artist, and The Ice Cream Social (1993–2008)—a multi-platform project which included a TV pilot for the Sundance Channel, a novella, installations, ceramics and performance—has been cited by Hans Ulrich Obrist as pioneering the “expanded exhibition.” Progressively evolving away from the prevailing model of the professional contemporary artist, in his books High Entertainment (2023) and Concrete Comedy: An Alternative History of Twentieth-Century Comedy (2011), he has identified and advanced “alternatives to art.” Among his six books are The Velvet Grind: Selected Essays, Interviews, Satires (1983-2005) (2006) and The Camera Believes Everything (1988). He divides his time between Shorewood, Wisconsin, and Bruxelles, Belgium

We stopped to chat for only a moment. “Gotta go,” he said, racing away. “Late for the orgy.” Biographies of contemporary art dealers are rarer than funny painters. There’s a book about Richard Bellamy and the 60s Green Gallery, and one about the legendary Leo Castelli. Now they have some company—an utterly human telling realized through group authorship, voices guided by love for a singular character and, it is hard not to feel, a vanished civilization as well.